Language Development

This was one of the first classes that I was asked to teach. Over the years it went through many modifications until about 8 years ago when it was completely redeveloped. That was in part due to the dramatic changes in cognitive science, brain research, and language theory.

For this class I used my background in linguistic anthropology, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, and primatology. (See my Masters paper for more.) In recent years I added new readings from brain neuroscience.

In the early years, this field of language development was awful, in my judgement. Existing textbooks were based on the IP (information processing) analogy in cognitive science, Chomskian generative grammar, and weak neuroscience. As I was learning the field, I included books like The Language Instinct by Stephen Pinker, which was based on those ideas, and which I now see as totally discredited.

With several scientific breakthroughs, including machine learning, construction grammar (Tomasello), Bayesian learning models, and advances in neuroscience, it was time for me to completely re-do the class. Perhaps surprisingly (but not to me), the structural grammars of Boas and students are now again appropriate, and I use that material too. I have still found no worthy textbook on language development. The lectures were all based on my readings.

Lectures

The Basics of Linguistics

This lecture is lifted largely from the introductory lecture of my Anthropological Linguistics undergraduate class, taught by Martha Hardman-de-Bautista. In later graduate school, her 9 hour ‘Field Methods’ course was a big influence on my understanding of language and cognition. Her influence can be seen throughout this course, but especially in Part 1 of Phonology and the Morphology lecture.

Articulatory Phonetics and Phonotactics. This is the anthropological linguistics that I learned first as an undergrad and then again in grad school. It is method as well as philosophy for language. My favorite, ‘No contrast, no understanding’.

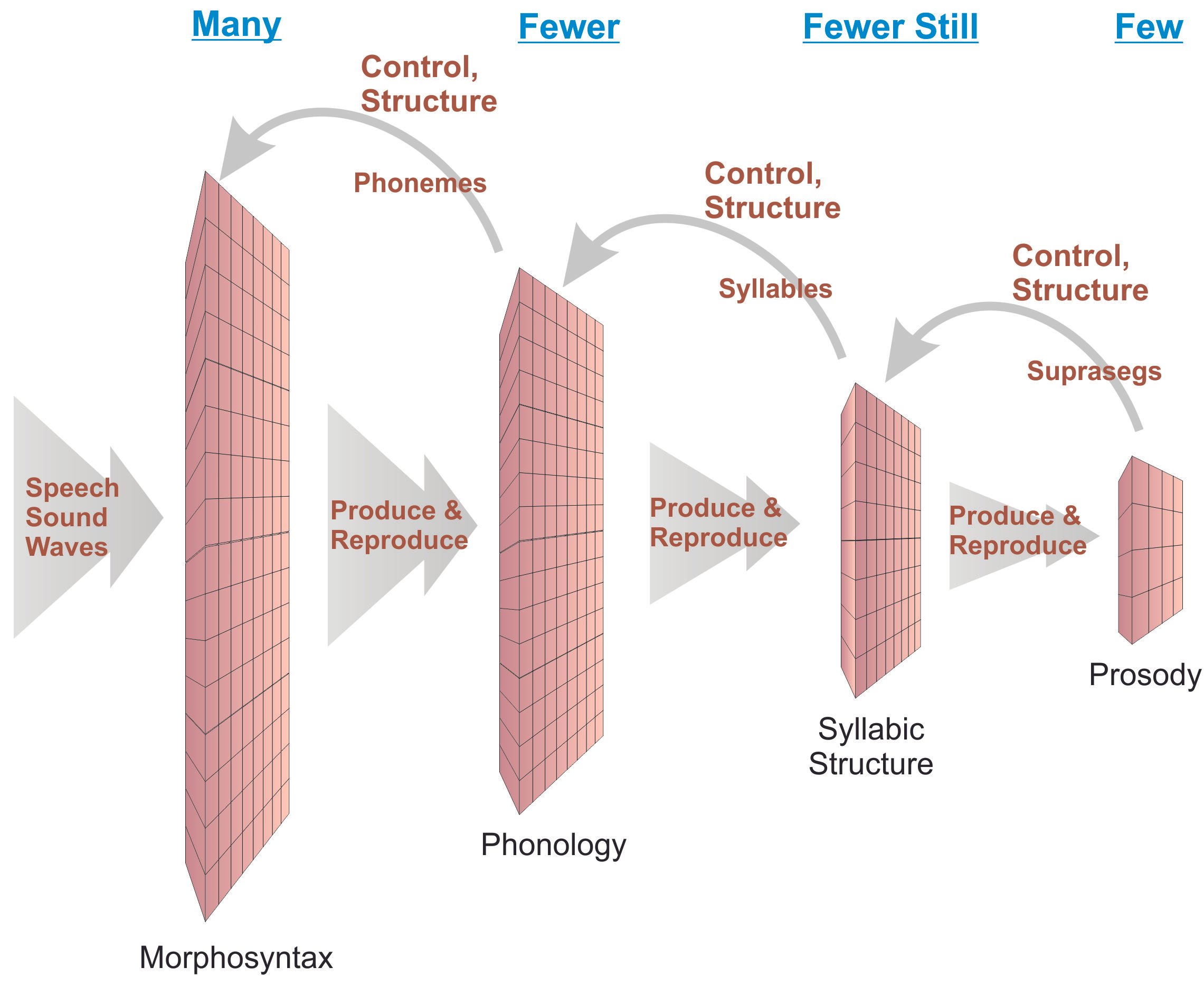

Acoustic Phonetics and Prosody. Acoustic phonetics with its high-tech tools has largely overtaken articulatory phonetics. Prosody and syllabic structure are additional scales of language sound. Living in a country with two tone languages (Mandarin and Taiwanese), it is necessary to think of language properties that apply to chunks of speech that are larger than phonemes.

There is a lot of Hardman in here. Her specialty was morphological variety and linguistic relativism. Morphology is the first layer of grammatical structure and it is implicit knowledge. Each language has its own morphological structures that define and channel thought. Some Mandarin morphology is included.

Basics of syntax - clauses, phrases, and words. Includes meaning in syntax. The meaning of the components of syntax can be described in new and interesting ways: Verb Syntax, Case, and Semantic Role.

Semantics, Pragmatics, and Mandarin Syntax. In the semantic view, syntax is not simply a set of formal rules. It is instead a network of conventional constructions – from words, to idioms, to abstract patterns of word types. This functional approach is today called construction grammar, or usage-based grammar, or cognitive functionalism.

Pragmatics studies the ways that social context and speaker goals contribute to communication. Communication depends not only on grammar and lexicon, but also on the context of the utterance, any pre-existing knowledge about those involved, their ‘common ground’, and the intentions of the speaker and others. These tools will help us comprehend gestural communication in apes and humans.

Most of my Taiwan students did not know that Mandarin has syntax! Of course it does. In fact, it is the most expansive component of its grammatical structure. What Mandarin lacks in morphology, it makes up for in complex syntax (another of Hardman’s principles of language, realized in Mandarin).

Ape and Human Gestural Communication

Gestural Communication in Apes

I love the fields of primatology and paleoanthropology as I learned them in graduate school. Knowing our human ancestors and our closest living relatives adds understanding of what we are. I was extremely happy when I found Tomasello’s book Origins of Human Communication (2008) that joined together my interest in primates with the study of language. Linguists had tried and failed for many years to teach human language to apes. They failed because language is not only speech but is first and foremost communication. Tomasello recognized that gestures are a channel of communication that apes (including humans) naturally possess.

With that understanding, human communication looks very different. It is no longer formal rules in mind. It is based on cooperation and social motivations for helping and sharing. It is therefore not surprising that we find its roots in the cooperative behavior of ape gestural communication, and that we see those abilities expanded in human gestural communication that begins in infants prior to speech, and that is never completely replaced by spoken language.

In this ppt, we create a ‘cooperation model’ of human communication from Tomasello, which depends on: Shared intentionality, Social motivations for helping and sharing, and Communicative intentions.

The three basic human communicative motives are for: Requesting, Informing, and Sharing (more in the Grammatical Development ppts below).

Predictive Processing and Neurolinguistics

Good riddance to the innate grammars of Chomski (and Pinker). Psychological experiments have shown that infants use general learning mechanisms to discover statistical patterns in the world. It is now believed that they use that ability to discover the patterns in speech, i.e., to learn the grammars of their languages. That ability is aided by another form of statistical learning, known as Bayesian inference. Like little scientists, children are good Bayesian learners. They produce models of the world for which they are constantly updating probabilities. Repeated throughout childhood, children gradually learn their languages (and cultures).

Another essential component of the new cognitive theories that support language and language learning is prediction. In my early computer science and cognitive science days, the dominant model of cognition was an IP analogy. That is ‘information processing.’ From computer science, the basic model of input-process-output, aided by a store of memory, was used to conceive of human cognition. Models of brains were imagined in which ‘programs’ and ‘memories’ could be located in brain areas and ‘called’ to commence processing of thought and language. Localized brain areas for speech ‘input’ and ‘output’ were identified.

Today, that approach is rejected. What was always missing from early cognitive psychology and the IP analogy was the feature of ‘learning’. How did those ‘programs’ and ‘data’ get into mind? Today, the new focus on ‘learning’ has changed all that. Through statistical learning, Bayesian inference, and predictive processing, we are understood to ‘construct’ our own minds in childhood and throughout life. In predictive processing, your brain works from the inside out, forming hypotheses and making predictions about the world. This ability is essential to mental life and language use.

Machine Learning and Neurolinguistics

For my Masters degree in the late 1980s, I learned the artificial intelligence of the day. Expert systems, natural language processing, and the newest member to the club, neural networks. Neural networks, I immediately recognized to be the most brain-realistic model, and also the missing piece to the IP cognitive science of the day because it was a computer model for ‘learning’.

After reading widely in the newer language and neuroscience literature, I settled on Lisa Barrett’s 2017 book, How Emotions are Made, for my guide. Today’s neuroscience has dramatically changed the way we understand brains. 86 billion neurons are connected into massive networks that never lie dormant waiting for a stimulus. Your neurons are always stimulating each other, sometimes millions at a time. Intrinsic brain activity is one of neuroscience’s great discoveries of the past decade. The brain is not a simple machine reacting to stimuli in the outside world. It is structured as billions of prediction loops creating intrinsic brain activity.

In the IP model of cognition, language is the product of ‘processing’ or parsing within dedicated brain modules. Today, instead, language is a product of whole-brain activity within networks of neurons. Language depends on learned knowledge, which is the product of experience, which is encoded throughout the cortex, and which is the source of predictions that facilitate processing in more specific language regions.

Language Development

The study of phonological development is the original domain of language development research. It is experimental, centered in psychological laboratories around the world. Research has followed the changing trends of language and brain theory explored in the preceding weeks. Its focus has been the production and perception of speech sounds prior to and following the beginning of speech. The research has used both articulatory and acoustic phonetics.

Grammatical Development, Part 1, The Grammar of Requesting

As might be expected, the study of the childhood development of morphology and syntax (grammatical development) has been dramatically transformed over the years, accompanying the fundamental shifts in the fields of linguistics and neuroscience.

Here is a fascinating assertion of the new construction and functionalist views of grammar: The communicative function of language creates the need for syntax. Language functions to meet our human needs to communicate and to cooperate to accomplish our goals. The purpose or motive for our communication determines how much and what kind of information needs to be ‘in’ the communicative signal. In other words, the function of our communication determines what things need to be in our message. And therefore, in a very general way, the motive for our communication determines what kind of grammatical structuring (morphosyntax) is needed.

Consider again the three major motives of human cooperative communication: Requesting, Informing, and Sharing.

Requesting typically involves only you and me in the here and now and the action I want you to perform. The simple words and gestures of requesting requires no real syntactic marking. Only a kind of ‘simple syntax’ in a grammar of requesting.

When informing, we intend to inform others of things helpfully. This often involves all kinds of events and participants displaced in time and space. I.e., Who did what to whom, and when! This requires some ‘serious syntax’ in a grammar of informing.

In sharing we want to share with others in the narrative mode (tell a story) about a complex series of events with multiple participants playing different roles in different events, at different times. We need even more complex syntactic devices to relate the events to one another. And to track the participants across the events. This leads to the need for ‘fancy syntax’ in a grammar of sharing and narrative.

In this ppt, the grammar of requesting is covered: Utterances and Words: Holophrases, Multi-word Utterances, and Two-word Combinations: Pivot Schemas.

Grammatical Development, Part 2, The Grammar of Informing and Sharing

This long ppt dives into the new grammar: Construction grammar, usage-based grammar, cognitive functionalism. The approach is fascinating as applied here to the other two motives of cooperative communication, informing and sharing. The story of how children construct their grammars is a new wonder of linguistics.

In the grammar of informing we see the beginnings of the child’s use of conventional syntactic devices: for identifying (when and what), structuring (who-did-what-to-who), and expressing (why). And so, informing creates functional pressure for doing such things as marking participant roles and keeping track of time. However, no particular devices are specifically determined by these functions, since different languages embody them in very different ways (languages solve these problems / functions in their own ways).

In the grammar of sharing, we see expressed the basic human motivation to simply share information, especially attitudes about the information, with others. A major way that people of all world cultures share information and attitudes with others in their group is in narratives. Basically all cultures have narratives that help define their group as a coherent entity through time – creation myths, folk tales, parables, etc. From a linguistic point of view, narratives that tell an extended story raise a host of problems: How to connect multiple events and their many participants… and across time (This happened first, later something else happened!). These problems are solved with a number of different syntactic devices of what we might call ‘fancy syntax’.

Language in Brain and Body

Body-Budgeting from the interoceptive network is the top-down, or inside-out connections that convey predictions from high-levels of the brain to lower-levels, and from lower-levels, out to the sensory surfaces. Your current goal at every moment in time is linked to the big four master motives and body-budgeting needs. But not directly linked. The means of satisfying your body-budgeting needs are in a hierarchy of control, the hierarchy of cultural models. You might think that in everyday life, the things you see and hear influence what you feel, but it’s mostly the other way around (according to Barrett): What you feel (on the inside, body-budgeting, master motives) alters your interaction with the world around you.

As you go through your day, you apply ‘concepts’ in a top-down manner to construct perception. At each step, concepts unpack as predictions. Cultural models are elaborate concepts. Concepts can also be very simple. Concepts are not fixed definitions in your brain, they are not prototypes of the most typical or frequent instances. Instead, your brain may have many instances of cars, of balls, of rides, of sadness, of love, or anything else, and it imposes similarities between them, in the moment, according to your goal in a given situation.

To build a purely mental concept (not physical), you need a secret ingredient: Words. More generally, we should label form-concept pairs as ‘linguistic constructions.’ Linguistic constructions can be words, conventional phrases (I dunno), idioms (kick the bucket), or more abstract constructions of patterns and words. How are concepts realized in neurons? How are concepts learned, and applied? Answers and much more are found in this last ppt, which ties up what we know about language development, grammar and language in the brain.